Another eighty million dead. How will politicians make amends to the animals?

(2/3) Doing Westminster Better in November 2023

This is Doing Westminster Better, my newsletter about what UK politics means for global priorities. Today, we’re looking at recent animal welfare news: I’m spotlighting the ways we’re failing our fellow creatures – like leaving eighty million chickens to die and weak fish welfare guidance – but also new opportunities to make amends to the animals – like a new Defra Secretary and a Cop summit with industrial agriculture finally under scrutiny.

You might also be interested in yesterday’s piece on Foreign Secretary David Cameron, or tomorrow’s piece on whether the Prime Minister’s bite is living up to his bark after the world’s first AI Safety Summit.

This can’t go on: eighty million Frankenchickens died prematurely

An investigation from Open Cages has revealed that 83.3 million Frankenchickens died before reaching slaughter weight in 2022. That’s a tragedy: over eighty million living creatures were bred into existence and endured great pain, just to die a meaningless death as a waste product. Here’s Open Cages’ Connor Jackson:

“These figures highlight the shocking scale of suffering and death at the heart of the UK’s chicken industry. Just like eggs from caged hens, Frankenchickens must go if we want to live up to our ambitions of leading animal welfare standards.” (source)

The eighty million represent a mortality rate of 7%, which exceeds the Red Tractor farm assurance scheme cap of 5%. They also represent an increase since 2021, when ‘only’ 64 million chickens died prematurely.

What are Frankenchickens, and why are they particularly likely to die early? Here’s what I’ve written about them before:

Frankenchickens are “genetically selected, fast-growing breeds”. Whereas a “standard organic chicken grows to its weight for slaughter in 81 days”, a Frankenchicken takes just 35 days. Weight for slaughter is such a sickly idea to me: a chicken’s natural lifespan is years. Of course, a Frankenchicken lives with endless ailments and maladies, like lameness and heightened risk of heart failure, so its “natural”, unslaughtered lifespan would still be short – and its short life would be miserable, especially because it would almost certainly be raised in factory farm (“intensive indoor rearing”) conditions, barely seeing the sun, and crammed in with fellow chickens more than densely enough to create psychological distress and heightened pandemic risk. Frankenchickens are the chickens we fucked up. They have, as The Humane League’s Sean Gifford says, “suffering in their DNA”.

We should acknowledge that these eighty million deaths are a result of our consumer demand – of British people’s expectation that we can eat substantially more chicken than we could just a couple of decades ago, and that the chicken will always stay cheap. This creates incentives to use fast-growing breeds, to cage chickens, to sacrifice animal welfare at the altar of profit. This wasn’t inevitable. It was an economic choice made by the UK, and we could still choose differently. Sometimes, people say a plant-based future is unimaginable because we’ve always eaten meat like this and always will. That’s so odd to me – we haven’t always eaten meat like this, and if we could survive without this quantity of factory farmed, artificially cheap chicken fifty years ago, then we can do it again!

Transitioning to a plant-based future, with or without plant-based or lab-grown chicken, will be critical in the long-run for animal welfare and environmental sustainability. But we could dramatically improve animal welfare today without turning anybody vegan by moving on from inhumane Frankenchickens.

Consumers usually say they want higher welfare standards, but they aren’t willing to put their money where their mouth is. And farmers usually say they would prefer better conditions, but they feel pressured to adopt the cheapest methods because their margins are thin. It’s not good enough for everybody to say they want better animal welfare when nobody is willing to act on that! If consumer preferences systematically go unmet, that’s market failure and the government would be right to step in, like by legislating against Frankenchickens. That’s what this opinion piece from The Mirror’s environment editor Nada Farhoud is calling for: “It's time to outlaw the cruelty of fast-growth chicken - too many animals suffer”.

In fact, it’s more than plausible that the government have already declared Frankenchickens illegal. UK law states that:

“Animals may only be kept for farming purposes if it can reasonably be expected, on the basis of their genotype or phenotype, that they can be kept without any detrimental effect on their health or welfare”.

I’m no lawyer, but I can’t see a way to square this rule with intensively farming Frankenchickens when we know their health is compromised by selective breeding. The Humane League UK have brought a legal challenge against Defra for failing to enforce this law. They lost a court challenge in May, but have been granted leave to appeal.

You can support Frankenchickens by:

Signing Open Cages’ petition to Lidl here, or applying to work with them in potentially high impact, no experience needed roles until 30 November here

Donating to The Humane League UK, who are running a matched funding campaign between 22 and 28 November.

Animal Law Foundation urge Scottish government to issue guidance on farming salmon

If chicken suffering matters because there’s so much of it, then we should pay more attention to the other animal that the UK farms at this dumbfounding scale: salmon. Scotland is the world’s third most prolific salmon farmer, and we know that in Scotland premature farmed salmon deaths doubled from 2021 to 2022 and unacceptably many farmed salmon are afflicted with flesh-eating lice. Now, The Animal Law Foundation has written to the Scottish government to urge them to step up and develop official guidance on ethical salmon farming.

Farmed fish are currently protected by some Scottish animal welfare legislation, but there isn’t any official guidance advising farmers on how to meet their legal obligations, as there is for terrestrial animals. There is a ‘Code of Good Practice’ developed not by the government, but by the fish farming industry.

The Animal Law Foundation write:

It is clear that official guidance is needed yet the Scottish government has argued it does not need one, due to the existence of the industry Code of Good Practice. However, when the Scottish Government has been asked to ensure the Code of Good Practice is enforced it has claimed it does not need to do this as it is not its Code. This is a CATCH-22 that needs to change. It is time to introduce official guidance, something the Scottish Government has the power to do under the law. (source)

What’s striking is that the ask isn’t stronger laws or even tougher enforcement mechanisms – just an ‘encouragement mechanism’, a nudge to show companies how to do the legal thing. Whether it’s taking Defra to court over Frankenchicken enforcement or writing to the Scottish government over fish farming guidance, there’s so much left to do for animal welfare even after laws are passed. The effective altruist in me sees high marginal impact in monitoring and evaluation work; the utopian anti-speciesist in me is depressed that even legal victories are far from practical ones.

It’s also important to note that farmed fish have too little legal protection in the UK, even compared with terrestrial farmed animals. We need to raise the legal standards for fish to be on par with the other animals, such as by mandating CCTV in fish slaughterhouses.

Steve Barclay is the new Defra Secretary

Thérèse Coffey resigned as Defra Secretary in yesterday’s reshuffle. The former campaign manager, Health Secretary and Deputy PM for Liz Truss, Coffey had been appointed to the environmental post when Rishi Sunak succeeded Truss as PM last year. She didn’t mention animal welfare in her resignation statement, instead writing:

As you know, Defra touches so much of our lives. It is the voice and guardian of nature, food security and our countryside communities. Just in the last year, I was pleased to publish our Environmental Improvement Plan, launch our Plan for Water, and help to secure the Global Biodiversity Framework in Montreal and the fund to deliver it. I have strengthened the foundations for Defra to deliver here in the UK and globally, such that this government has achieved more than any other to protect our planet. Having a sustainable farming and food sector is critical for our long term food security, and by listening to farmers and making changes, I am confident we can deliver that sustainability and strengthen both our farming and fishing sectors. As for our rural communities, unleashing rural opportunity and championing the countryside is a core Conservative principle that will endure.

She’s being replaced by Steve Barclay who, in an odd twist (or a sign that the Tories are really running low on candidates), had previously replaced her as Health Secretary. Barclay’s already attracted criticism for taking a £3000 donation from the head of a climate-sceptic think tank and for his wife’s links to Anglian Water; Defra is responsible for monitoring water companies and Anglian Water has been accused of illegally polluting rivers by dumping wastewater. Barclay claims to be committed to the government’s net zero targets despite his link to climate scepticism.

A new Defra Secretary is a new opportunity for animals. To properly secure an animal-friendly UK, the anti-speciesist movement will need to win the hearts and minds of the public at large. A few particularly influential voices, especially politicians, can have an outsized influence steering us towards those better shores. But that said, a revolving door of Defra Secretaries means that priorities keep getting reset and jumpstarted, and that animals and the environment are done an injustice by the government’s lack of continuity and commitment.

Here’s Claire Bass, of the Humane Society, on the situation:

“Steve Barclay is the third Defra Secretary of State in just over a year and while Whitehall has seen plenty of changes in that time, the same can’t be said for animals in this country who continue to be let down by policymakers. In two and half years the Government has delivered less than a third of its own Action Plan for Animal Welfare and has broken several commitments to protect animals, including a hugely popular manifesto pledge to ban imports of hunting trophies.

Defra Secretary is an enormously important role, responsible for the health and welfare of billions of animals in this country. Animals deserve more than just warm words from Ministers about the UK being a ‘nation of animal lovers’, they need a Secretary of State who will deliver action, starting with the swift introduction of the promised Bill to ban live exports, and firm resolve to pass a hunting trophies ban into law.” (source)

Government recommits to live animal export ban

Here’s Barclay’s first opportunity to do better for the animals. Politics watchers will be well aware that Sunak’s government recently had a King’s Speech – an opportunity to lay out their legislative agenda. This included a recommitment to ban live animal exports, a long-time ask from the animal advocacy community which is widely supported by the British public. 87% of respondents to Defra’s public consultation supported a ban on live animal exports.

In 2019’s Get Brexit Done election, Barclay Tweeted “It is impossible to ban cruel live animal exports while we remain in the UK” and pledged that a post-Brexit Conservative government would get the ban done.

The new commitment is being praised by animal advocates. The RSPCA say:

“It is imperative that this UK Government bans the live export of animals - outlawing the long, crowded journeys, mental exhaustion, physical injury, dehydration and stress that are a reality for farm animals on these unnecessary journeys [...] We urge the new Secretary of State to get this issue at the top of his in-tray and ensure this law finally becomes a reality.” (source)

I really recommend reading in full this piece from Philip Lymbery, chief executive of Compassion in World Farming. It’s clearly emotional for him to see a decades-long advocacy project almost come to fruition. He writes:

“In echoes of sentiments expressed by generations of campaigners since the 1990s, the Bill aims at “stopping… this unnecessary trade”. Yep, “unnecessary”. How many times have we rammed home that message, only to see it continue regardless? The nation’s animal welfare credentials sacrificed on the altar of economic expediency. Well, now it seems, things are different. And thank goodness.”

But the RSPCA, CIWF and the rest of the UK animal advocacy community are wary. A ban on live exports was a pledge in the Conservatives’ and Labour’s 2019 manifestos, and it was dropped in May when the government discarded the Kept Animals Bill. Lymbery is cautiously optimistic – “I know, I know, we’ve been here before, but somehow, this time feels more real. The language surrounding it feels more committed.” – but animal advocates know that, even with broad public support and bipartisan manifesto commitments, nothing is certain.

Cop28 to discuss animal agriculture

And here’s Barclay’s second opportunity. When Cop28 takes place in Dubai at the end of this month, industrial animal agriculture will finally be on the agenda at a United Nations climate change conference. We know that Big Ag is the second largest greenhouse gas contributing industry, and that ‘climate-friendly meat’ is an illusion: to save us from climate change, the developed world’s diets will have to shift away from environmentally damaging factory farmed meat.

Meat is an emotionally charged political image, and politicians across the world are wary of looking anti-meat – or even choose to exploit pro-meat sentiment. The Guardian describe this phenomenon well in their editorial, which I’ll quote at length:

while the science is stark and straightforward, the politics is anything but. Agriculture is a sector where economic interests overlap with cultural traditions, national identities and sentimental attachments to the land. It was telling that when Rishi Sunak was desperately searching for green policies to oppose this autumn, he chose to invent a fictional “meat tax” proposal to suit his purposes. Mr Sunak was nakedly and disreputably seeking to create net zero dividing lines ahead of the next election. But across the west, more principled politicians than him are struggling to show leadership on fraught and sensitive terrain.

In the United States, Joe Biden has introduced new requirements to reduce methane emissions in fossil fuel industries, but they did not extend to the vast American beef industry. Last spring, the Dutch Farmer-Citizen Movement – set up in protest at government plans to reduce livestock numbers by a third – sent shock waves across Europe when it won regional elections. In Ireland, where farming makes up almost 40% of all emissions, proposals for similarly dramatic culls have been discussed behind closed doors in government, but not approved as policy. Compared with sectors such as transport and construction, the green transition in agriculture is notably underpowered. (source)

Frankly, your government doesn’t have a worthwhile environmental doctrine if it doesn’t have any policy to address Big Ag. If politicians lean into anti-environmentalist agri-populism, they’ll be condemning humans and wild animals to the ravages of climate changes and condemning billions of farmed animals to lives of torture and exploitation.

Reports of declining British meat consumption are greatly exaggerated

UK meat consumption at lowest level since records began, reports The Guardian amongst others. This is true – but it’s not actually good news for animals.

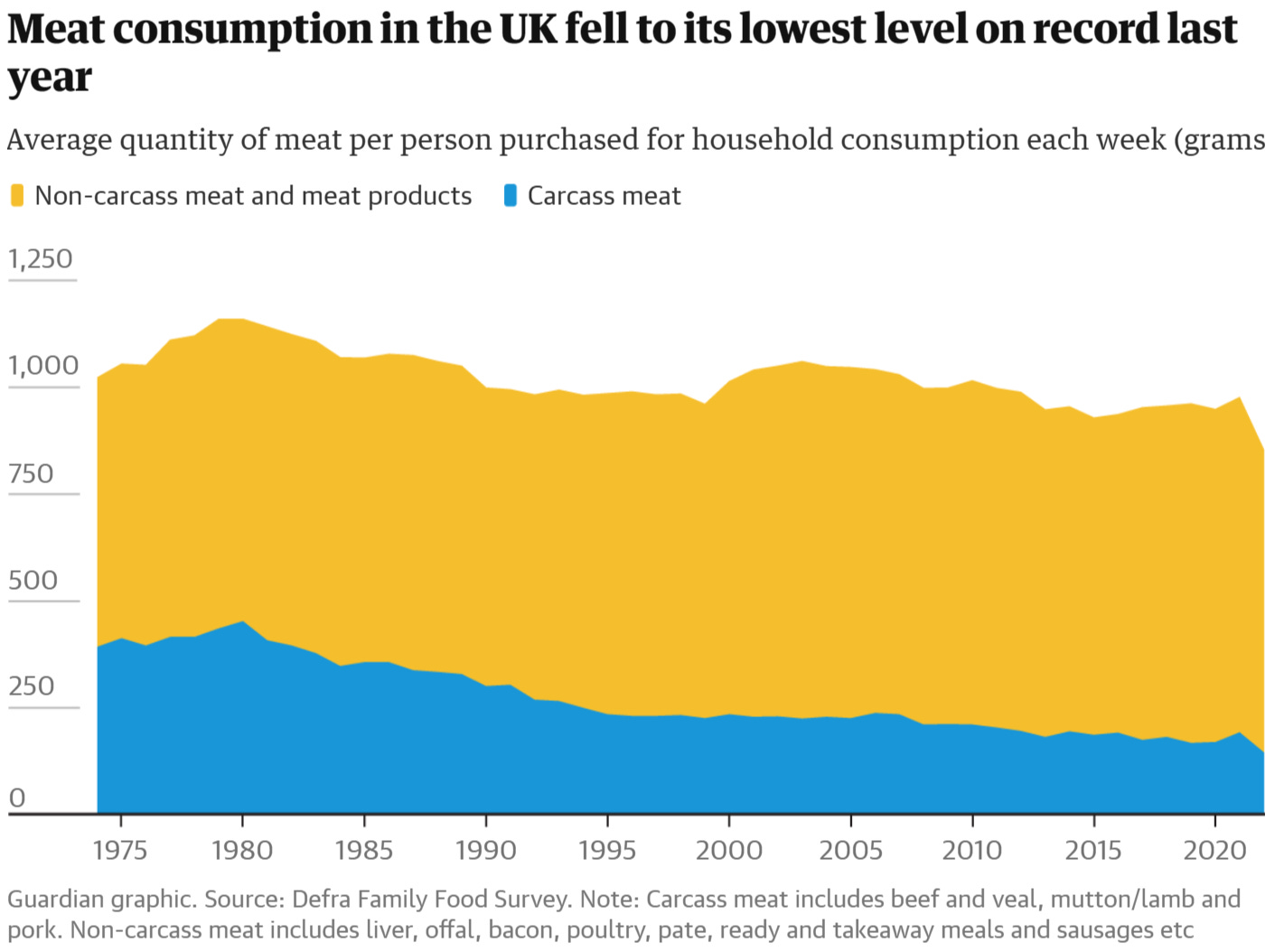

The average Briton ate 845g (1.88lbs) of meat a week in the year to March 2022. That’s a drop from 976g/week the previous year. The decline over the years doesn’t look very steep when you graph the data (I’ve copied The Guardian’s graphic below), but it’s there.

Actually, you’ll notice the drop in carcass meat is somewhat steep, but it’s made up for by an increase in non-carcass meat. That’s a problem. Non-carcass meat here includes poultry; over time, British diets have shifted towards chicken meat. As chickens are such a small animal, this means that even as average meat consumption by weight has declined, we are farming and slaughtering more animals by an order of magnitude.

Today, 98% of farm animals in the UK are chickens and 95% of them are factory farmed. If you eat meat and don’t agree with factory farms, you’re almost certainly supporting them anyway.

This is why commitments to improve the lives of chickens, like the Better Chicken Commitment or getting Defra to enforce the law against Frankenchickens, are especially high scale opportunities for impact. Not just millions, but billions of lives are at stake.

Alternative proteins: experts say we need them, consumers say some of us want them

Concerned experts have written an open letter to the PM arguing that the UK should “make a £1 billion ‘moonshot’ investment between now and 2030” to fund the alternative proteins transition. Signatories included:

Nobel Laureates: Sir Christopher Pissarides, Sir Roger Penrose, Sir Richard J. Roberts, and Sheldon Lee Glashow

Other prominent scientists like Sir Ian Boyd (President of the Royal Society of Biology) and Lord Martin Rees (Astronomer Royal and co-founder of the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk)

Animal welfare and environmental campaigners like George Monibot, Chris Packham, Dale Vince (who has courted political controversy in the UK for funding Just Stop Oil and the Labour Party), and Philip Lymbery (CEO of Compassion in World Farming)

Christiana Figueres, a diplomat who has extreme credibility in environmental public policy for her work negotiating the lead-up to the Paris Accords as Executive Secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

As well as the moonshot investment in plant-based, fermented and cultivated meats, and “alongside much needed regulatory, tax and labelling refinements,” the letter calls on the UK government “to collaborate with the EU to turbocharge the commercialisation of a British sustainable protein industry situated in a wider European hub of innovation”. I can’t imagine Brexit voters being too keen on working on fake meat with Brussels – but I also can’t see many other options. The UK and Europe have to shift towards a plant-based food system and, in rejoining the Horizon programme and initiating public AI safety research, we’ve recognised that science is at its best when it's an international effort.

New research has been published on alternative proteins in the UK. Bryant Research, a pro-alternative proteins research organisation, ran a poll of 1000 Brits to investigate consumer attitudes to plant-based meat. The Social Market Foundation have published ‘Putting intensive farming out to pasture: Can alternative proteins reduce farmed animal suffering?’, a new report including projected sales for alternative proteins.

The SMF report is the last in a series of three on animal suffering in the UK. I’ve been so pleased to see a reputable policy think tank talking about animal welfare as an object of political concern. Much credit to the RSPCA for sponsoring this work, and to Jake Shepherd, Aveek Bhattacharya, and the team.1

I recommend clicking through and digging into the details of both reports. One fact to highlight from Bryant Research: 43% agreed or strongly agreed that “I don’t see any reason to replace conventional meat”.

Forecasts gathered by the SMF vary: experts predict between 3% and 70% of the global meat market will be alternative proteins by 2040. This hinges on whether cultivated meats take off; in scenarios where lab-grown meat fails to scale, the average forecast drops from 32% to 14%. On the one hand, cutting out a third of the global meat market could be the biggest victory achieved by the animal advocacy movement, but on the other hand, even this would only mean keeping the quantity of farmed chickens approximately equal to the number today. We have a long way to go before we reduce aggregate animal suffering. The first step is to stop increasing it.

I also appreciate the SMF suggesting that the alternative proteins space should keep its distance from the emerging insect farming industry. Insect sentience is uncertain but plausible, and we should adopt a precautionary principle to avoid stumbling into “ethical concerns that could be catastrophic for animal welfare”. Not only are insects small enough to re-create the small-bodied animal problem (as discussed in the chicken context above) at an even worse scale, but there are political and practical limitations to the animal advocacy movement aligning with insect farming: many insects are farmed for animal feed, propping up the economic power of Big Ag; and most people simply don’t want to eat insects anyway!

What it would mean for the UK should lead on animal welfare policy

If you’re an MP looking to make the UK better for animals, what should you do?

Two answers are obvious from I’ve already written:

You should support the ban on live animal exports. And don’t just support it at the King’s Speech – support it all the way through, and make sure that this time the government actually live up to their manifesto pledge

You should back the alternative proteins industry. The SMF report contains specific policy recommendations, including public funding for R&D.

But if you’re looking for more suggestions, philosophy professor Jonathan Birch has written some suggestions that he thinks should attract bipartisan support, and can mutually “benefit consumers, producers and animals”. Philosophy can be pretty abstract, but Birch researches public policy from a philosophical angle and contributed important foundational research to the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act. I strongly recommend reading his thoughts on policy, including food labelling, selective breeding, and replacing animal research.

The way we treat animals remains one of the biggest, yet most neglected, problems in UK policy today. People like eating meat and they like it when meat is cheap, but we know that when people confront the reality of Big Ag, they want it to change. Wide public support for banning live exports is just one example. If politicians want to be leaders, they should help the UK live up to what we expect of ourselves, and foster a society that truly loves animals.

I was interviewed by the SMF at an early stage of this project, and this report cites research on which I worked.